An Examination Of Textual Evidence Regarding The Imposture

Christopher Marlowe, wounded child of the angels, you are made immortal with a kiss.

Although the nature of the Shakespeare-X Message allows a mathematical probability calculation which is a conclusive proof, and the validity of this mathematical proof requires no subjective literary supporting evidence whatsoever, nevertheless during my researches confirming the Shakespeare-X Message, I have also come across a great many new supporting arguments which take the more traditional forms of humanities research.

These arguments number in the many dozens, although only a select few are presented here.

My interest is not to make anything resembling an exhaustive list here,

this will be the future work of the entire corpus of Shakespearean scholarship for the coming decades. Shakespeare-Marlowe’s literary works are riddled with allusion to his complex personal situation.

And so for interest only, I have included a few of these newly arising references here below.

Some Interesting Examples Of Textual Evidence:

1. The balcony speech in Romeo and Juliet. Act 2, Scene 2, L847-853, First Folio, 1623.

JULIET:

What man art thou that thus bescreen'd in night

So stumblest on my counsel?

ROMEO:

By a name, I know not how to tell thee who I am:

My name deare Saint, is hatefull to my selfe,

Because it is an Enemy to thee,

Had I it written, I would teare the word.

Here Shakespeare-Marlowe directs us to the Shakespeare-X Message when he directs us to write down his name and ‘tear the word’ in order to tell us who he is.

A moment’s consideration leads us to notice that this is a rather odd thing to say in the situation of an outdoor romantic seduction, when no-one has either pen or paper available, or on their mind.

Shakespeare-Marlowe was a very experienced and expressive writer, we should always assume that he is saying precisely what he means to say. This is not a writer whose literary control is suspect.

This balcony speech of course also contains many other famous references to the question of dishonored names, and name relevance in general. ‘What’s in a name’ / ‘A rose by any other word would smell as sweet..’ / ‘Thy name which is no part of thee’ etc.

Clearly while writing this speech Marlowe has his sullied name repeatedly on his mind, and apparently the hidden location of the Shakespeare-X Message as well.

2. The London Prodigal, author unknown c1604

This play, which title is telling, has a discredited attribution to Shakespeare. It is a play of low literary quality, clearly not written by the poetic genius Shakespeare-Marlowe.

The historical record shows that the play was performed for King James I by the King’s Men in 1604, and in this context it is possible that it was written by the Shakespeare-Marlowe playing company as a plea to the new king to allow Marlowe to return to England from exile. The play shows a cheerful spirit.

Queen Elizabeth died in 1603, and so with a new king on the throne there existed a new opportunity for the theater company to bring Marlowe back from exile. The King’s Men were in favor of the crown at this time.

The play was published in quarto in 1605, under the name William Shakespeare, possibly even by the King’s Men as a way of attaching it in tribute, comic-spirited or otherwise, to the Shakespeare-Marlowe legacy.

It is telling that it was not included in the First Folio of 1623. Someone, almost certainly Marlowe, knew to exclude it because it was not his play and it was of low quality.

The plot of the play is that a prodigal son is brought to repentance, return and re-acceptance by his father, a responsible man named Christopher and called KIT in the play, (as was Marlowe by friends in real life).

In the play Kit is a man who pretends to be dead and reappears in another identity. This is a concept which echoes throughout the entire Shakespeare-Marlowe literary legacy.

The wayward son is named Matt, a name which has some indirect echoes of the name Kit. Subsequently in the course of the drama Kit asks for a pardon.

The play may readily be interpreted as the chastising response of an older Marlowe towards the wayward behavior of the younger Marlowe. The play shows contrition for past offenses.

From early in the opening scene of the play:

The London Prodigall Act 1 , Scene 1 L 80,

FATHER (KIT)

I am a Saylor come from Venice, and my name is Christopher.

This appears to be an undisguised statement of the intent of the play.

Also of the possibly real location of Marlowe.

3. Twelfth Night, Act 2, Scene 5, Modern text.

Twelfth Night is a play with a plot revolving around extremely confused mistaken identity

As the plot develops, a name written in a letter must be correctly deciphered by a group of people in order to further a romantic subplot. (Note the literary allusion.). The name is indicated only by the letters M, O,A,I. These letters are separated by commas in the First Folio.

The modern text states: in Act 2, Scene 5, L1115:

MALVOLIO: With bloodless stroke my heart doth gore, M,O,A,I. doth sway my life.

FABIAN: (Aside): A fustian riddle.

Some discussion ensues regarding each letter, one by one, until L1145 at which Malvolio states:

MALVOLIO: M,O,A, I. This simulation is not as the former:

and yet to crush this a little, it would bow to me, for

every one of these letters are in my name.

Malvolio is intended to be a figure of fun and so it’s appropriate that the crushing of these letters will not produce anything resembling his name.

What is particularly interesting is that when these same letters, MOAI are pronounced aloud as a single word, they do sound like a name crushed. The name MORLEY. (Pronounced MO’AY)

One should realize here that it is characteristic of many regional English accents to drop soft sounding letters in pronunciation for rapidity of speech, including the letter R. And also to soften the L sound.

Therefore Marlowe probably pronounced the RL sound of his surname softly if at all, as if swallowing it, as is common in English regional accents.

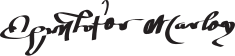

In his only extant signature Marlowe spells his name Christofer Marley, giving a clear indication that he pronounced the final syllable of his name with an ‘I or Y’ sound, and not an ‘O’ sound, as we do today.

The different spellings of Marlowe’s name appearing in the historical record give an indication of how the name was generally pronounced by people at the time, since spelling was normally phonetic then. Among others, these pronunciations range from MORLEY – MORLI – MARLY - MARLIN – MARLEN – MARLEY.

All of these spellings, which necessarily must have been transposed from speech, place the accent on the first syllable MOR/MAR, allowing the final syllable to tail off indeterminately into a clear ‘I’ or ‘Y’ sound.

Often in regional English pronunciation the sounds MOR and MAR are pronounced similarly, with an actual vowel sound lying somewhere between ‘O’ and ‘A’. As if the actual spelling was MOARLY.

This vowel sound would be understood differently by people of different English regional accents, as sometimes signifying MOR and sometimes MAR. Just as is still true today.

This is what accounts for the varying spellings of the first syllable MOR and MAR in the recorded documentations of his name. People transposed his name as their particular regional ear caught it.

It should be noted that even though the pronunciations would have varied by local accent, all of the documented spellings indicate an ‘I or Y’ sound ending the name, rather than the ‘O’ sound of today.

(This is also true of the Cambridge University use of the word as MARLIN – an N sound following a strong I or Y sound is so soft and subtle as to be easily subject to mishearing or imagining.)

Since Marlowe himself spells his name MARLEY, and it appears to have been heard and spelled by people as beginning with both MOR and MAR, it seems quite likely that he himself pronounced his name in an indeterminate manner, as MOARLI, causing the confusion of spelling.

The names Marley and Marlowe are still commonly pronounced in this way to this day in regional England. Furthermore, in Elizabethan times regional accents were generally thicker than they are today, due to the local isolation of populations.

Therefore there is quite some likelihood that Marlowe in fact pronounced his own name quite similarly to MOAI, as if it was spelled MOARLY, and was sounded very close to MO’AY, when he was speaking in his normal Canterbury accent.

In light of this subtextual interpretation, the actual dialogue in this Twelfth Night scene makes a great deal more sense than it does as it stands in the play text.

Marlowe appears to deliberately have his own name verbally stated aloud on the stage in this scene as the one who ‘sways the life’ of the characters.

4. The Jew Of Malta by Christopher Marlowe.

The Jew of Malta was written by Marlowe around 1589-90 and registered in 1594. It contains many thematic echoes of the later, superior play by Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice.

Despite being registered in May 1594, almost exactly a year after Marlowe's disappearance, it seems not to have been printed until 1633, almost 40 years later.

The play contains a prologue, spoken by a character named Machievel.

Marlowe had reputedly been commonly and publicly referred to in association with Machiavelli.

Here is the opening prologue, in which the character Machievel opens the play by declaring that the world thinks him dead and his friends guard his name from their tongues.

Prologue:

Scene, Malta.

MACHIAVEL.

Albeit the world think Machiavel is dead,

Yet was his soul but flown beyond the Alps;

And, now the Guise is dead, is come from France,

To view this land, and frolic with his friends.

To some perhaps my name is odious;

But such as love me, guard me from their tongues,

And let them know that I am Machiavel

This character, Machiavel appears in the prologue but nowhere in the play. Which is an unusual thing in any play. That a named character is not in it.

It also means that the prologue could easily have been added at a later date.

There is evidence to suggest that this may have been a practice of Shakespeare-Marlowe, this later rewriting of a play into a final form for publication. It would not be at all unusual for a literary writer to revisit his oeuvre for revision as age approaches.

Such a work method may easily have given rise to the two competing texts, A and B for Doctor Faustus, and also the competing texts for King Lear, Hamlet and other Shakespeare plays.

5. James Mabbe's elegiac from the First Folio, 1623.

To the memorie of M.W.Shakes-speare.

WEE wondred (Shake-speare) that thou went'st so soone From the Worlds-Stage, to the Graves-Tyring-roome. Wee thought thee dead, but this thy printed worth, Tels thy Spectators, that thou went'st but forth To enter with applause. An Actors Art, Can dye, and live, to acte a second part. That's but an Exit of Mortalitie; This, a Re-entrance to a Plaudite. |

|

J. M. |

Mabbe appears to make a clear statement that Shakespeare-Marlowe was thought dead and then reappeared.

6. Two Gentlemen Of Verona, Act 1, Scene 2. L 283-288, First Folio, 1623.

This play is of uncertain date of authorship. It was first published in the First Folio of 1623.

It is the first of the Shakespeare plays in which a heroine impersonates a boy.

The play is of Spanish sources and set in Italy for no apparent reason.

In Act 1, Scene 2, Julia tears up a love letter from Protheus, a man she secretly admires, and then examines the pieces regretfully.

JULIA:

283 Loe, here in one line is his name twice writ :

Poore forlorne Protheus, passionate Protheus:

285 To the sweet Iulia: that ile teare away:

And yet I will not, sith so prettily

He couples it, to his complaining Names;

Thus will I fold them, one upon another;

This is a precise description of what Marlowe did when creating the Shakespeare-X Message. He wrote two names in one line and then folded them together.

7. As You Like It, by William Shakespeare, 1599-1600

This play contains the only fully formed speaking character named William which Shakespeare-Marlowe ever created.

It also contains a Clown character, a Court Fool named Touchstone.

A touchstone was a stone used to authenticate precious metals, particularly gold. To guard against the counterfeit.

Touchstone, the Clown, is identified in the dramatis personae as Clown alias Touchstone, an unusual way for one of Shakespeare’s characters to be designated, with an alias given for no plot reason.

In the play Touchstone describes himself as ‘like Ovid among the Goths.’ Ovid was Marlowe’s favorite poet and was banished from Rome for his outspokenness. As was Marlowe from London.

The character Touchstone appears to represent Marlowe himself, who is specifically alluded to by Touchstone in the famous quote of Act 3 , Scene 3, L 1623-5.

CLOWN: When a mans verses cannot be understood, nor a mans good wit seconded with the forward childe understanding: it strikes a man more dead then a great reckoning in a little roome.

Outside the context of Marlowe’s real life concern for his literary legacy, these lines make little sense for the character Touchstone.

Touchstone’s verses can be readily understood and forwarded to future generations. Only Marlowe’s cannot. Inside that real life context the line make perfect sense.

In the play, the two characters, Touchstone and William meet for a hostile encounter in which Touchstone upbraids William for his ignorance.

In this encounter of Act 5, Scene 1, L 2380-2386, First Folio, Touchstone states:

CLOWN: Give me your hand: Art thou Learned?

WILL: No sir.

CLOWN: Then learne this of me, To have, is to have. For

it is a figure in Rhetoricke, that drink being powr'd out

of a cup into a glasse, by filling the one, doth empty the

other. For all your Writers do consent, that ipse is hee:

now you are not ipse, for I am he.

From the Latin, ‘ipse’ translates as ‘I myself’ or ‘self’. It is a root of the word solipsism.

This speech makes absolutely no sense in the context in which it is presented. In the play William is an ignorant country peasant who has no relationship to writing or writers whatsoever.

Why would Shakespeare have Touchstone declare himself in this manner, to be ipse among Writers, rather than William being him?

Either this is uncontrolled writing lacking any logic or sense, or the writer is saying it for a reason. And Shakespeare was not an uncontrolled writer. He is so naturally facile in expression that we must always assume he is saying precisely what he means to say. He has proven his intellect and literary skills a thousand times over.

These lines can only be properly understood as an indirect declaration of authorship by Marlowe via Touchstone, (the authentication stone). The authorship imposture is a matter which seems to have been weighing on Marlowe’s mind during the writing of this play, as evidenced by the repeated allusion to Marlowe and his situation, and his characterization of himself as a Court Fool.

8. Shakespeare-Marlowe's Obsession With Names.

Marlowe was obsessed with the subject of names, as well he might be. Often in the text of the plays he directs us towards the situation of the imposture and his lost name, honor and immortality. Sometimes he directs us towards the Shakespeare-X Message.

The word 'name' is one of the most frequently occurring words in the entire First Folio, appearing greatly more frequently than one would expect.

Here are some brief quotes on the subject of names taken from the texts of the Shakespeare plays. There are scores of them in the Shakespeare canon.

HAMLET

Act 5 scene 2 – The final scene in which Hamlet dies

Hamlet. As th'art a man, giue me the Cup. 3829Let go, by Heauen Ile haue't. 3830Oh good Horatio, what a wounded name, 3831(Things standing thus unknowne) shall live behind me. 3832If thou did'st ever hold me in thy heart, 3833Absent thee from felicitie awhile, 3834And in this harsh world draw thy breath in paine, 3835 To tell my Storie.

OTHELLO

Iago. Good name in Man, & woman (deere my Lord) 1769Is the immediate Jewell of their Soules; 1770Who steales my purse, steales trash: 1771'Tis something, nothing; 1772'Twas mine, 'tis his, and has bin slave to thousands: 1773But he that filches from me my good Name, 1774Robs me of that, which not enriches him, 1775And makes me poore indeed.

Oth. By the World, 2030I thinke my Wife be honest, and thinke she is not: 2031I thinke that thou art iust, and thinke thou art not: 2032Ile haue some proofe. My name that was as fresh 2033As Dians Visage, is now begrim'd and blacke 2034As mine owne face. If there be Cords, or Kniues, 2035Poyson, or Fire, or suffocating streames, 2036Ile not indure it. Would I were satisfied.

KING JOHN

Bast. A foot of Honor better then I was, 193But many a many foot of Land the worse. 194Well,now can I make any Ioane a Lady, 195Good den Sir Richard,Godamercy fellow, 196And if his name be George, Ile call him Peter; 197For new made honor doth forget mens names:

KING LEAR

Edg. Know my name is lost 3074By Treasons tooth: bare-gnawne, and Canker-bit, 3075Yet am I Noble as the Aduersary 3076I come to cope.

RICHARD II

Thomas Mowbray Duke of Norfolke :

Mow. No Bullingbroke: If euer I were Traitor, 495My name be blotted from the booke of Life, 496And I from heauen banish'd, as from hence: 497But what thou art, heauen, thou, and I do know, 498And all too soone (I feare) the King shall rue. 499Farewell (my Liege) now no way can I stray, 500Saue backe to England, all the worlds my way

COMEDY OF ERRORS

E.Dro. O villaine, thou hast stolne both mine office 674 and my name, 675The one nere got me credit, the other mickle blame: 676If thou hadst beene Dromio to day in my place, 677Thou wouldst haue chang'd thy face for a name, or thy 678 name for an asse.

THE WINTER'S TALE

Pol. Oh then, my best blood turne 532To an infected Gelly, and my Name 533Be yoak'd with his, that did betray the Best: 534Turne then my freshest Reputation to 535A sauour, that may strike the dullest Nosthrill 536Where I arriue, and my approch be shun'd, 537Nay hated too, worse then the great'st Infection 538That ere was heard, or read.

MERRY WIVES OF WINDSOR

Mis.Page. Letter for letter; but that the name of 615Page and Ford differs: to thy great comfort in this my- 616stery of ill opinions, heere's the twyn-brother of thy Let- 617ter: but let thine inherit first, for I protest mine neuer 618shall:

THE TEMPEST

Prospero: One word more: I charge thee 607That thou attend me. Thou dost here usurp The608 name thou ow'st not, and hast put thyself 609Upon this island as a spy to win it 610From me, the Lord on't.

TITUS ANDRONICUS

861For no name fits thy nature but thy owne.

Please Note:

None of these interpretative aspects are required to prove the case that the Shakespeare-X Message is proof of an authorship imposture perpetrated by Christopher Marlowe. This has already been proven mathematically elsewhere. This additional evidence is presented as matters of interest only, and to indicate directions for future academic research.

Also because it's an interesting list.